Investing Lessons from My Father

The vast majority reading this midyear missive are aware that John Bodnar, Jr., my larger-than-life dad, died as peacefully as he could July 24 at 10:35 p.m. Although he suffered from physical pain for several years, he did not suffer as they say, “at the end.”

He went uncharacteristically quietly into the night. As my daughter Jackie said to my brother Glenn later that evening: “Well…. heaven just got a lot more opinionated.”

John Jr. was 37 days short of his 88th birthday – not a bad run for a guy who spent his life in the diesel-engine room of naval vessels, in various chemical and oil refineries throughout New Jersey, and smoking for 60+ years.

He continued to smoke until the night before his heart bypass in 2006, when outside of New York City’s Lenox Hill Hospital, he flicked his final cigarette. He said to me, “that’s that,” and dropped his 60-year vice with the cocky confidence he exhibited his entire life. And he never picked up a cancer stick again. Amazing.

His wake, funeral, and burial followed the traditions of the Russian Orthodox Church like those of his parents, grandparents and great-grandparents. It was awash in fragrant burning incense, cantor-led lamentations of blessed repose, transgressions, paradise and Vičnaja pamjat – memory eternal. The smell of burning incense is like a time machine for me. The family history book just opens, and hundreds of memories, stories, and feelings come pouring out.

My dad was born in 1931, a classic depression baby. His parents, like almost all the adults in his Eastern European neighborhood, spent their lives waiting for the next depression. It was a constant refrain throughout his childhood: “It’s going to happen again, be ready, hide your money.”

The irony of my father’s childhood – in fact his entire generation’s childhood – was that they thought they were heeding the lessons of history, when all they were really heeding was their parents’ myths. In doing so, they were being deeply ahistorical. Specifically, they were ignoring the compelling lessons of their own parents and grandparents’ lifetimes on earth.

The reality during my dad’s life was the exact opposite. And somehow, he rejected the pessimism of my grandparent’s generation. He and my mother adopted a fiercely optimistic view that life (especially in America) is always improving, and they drilled into their sons that our goal should be to improve our lot in life. Every generation is to TOP the prior generation. And coming from a neighborhood of hard-working Ukrainians who viewed “WORK” as man’s natural state, they had to work harder and smarter to top their parents. And so they did.

The hard work part is easy for those of us with “the work gene.” When you have that gene (or the curse) you see work EVERYWHERE. Sometimes the hard part is to stop working. The smarter part for my dad was letting the capital markets do some of the heavy lifting.

Large cap equities have been an extraordinarily effective way for my family to build and protect our family’s purchasing power throughout the past 80 years – first as accumulators and later as retirees. His success even converted his own dad to begin buying equities later in life. My dad leaves behind a big holding in Merck common stock that was left to him by his own father.

As your trusted financial advisor, I share with you a phenomenal set of data, which I plan to share regularly with you – updated to the present moment – as a postscript to my father’s life.

Since my father’s birth in 1931 and my birth in 1958:

| Consumer Price Index Up | S&P 500 Index Up |

1931-birth of JB2 | 17x | 186x |

| 1958-birth of JB3 | 9x | 71x |

What are we to conclude from the numbers above? Inflation has increased the daily cost of living during my father’s lifetime by a factor of 17. During those same 87 years, the S&P 500 index increased by a factor of 186. That is NOT a typo.

Mainstream equities have been an extraordinary effective way for long-term investors to build and protect purchasing power for themselves and their families. My father and his father before him didn’t call it “multigenerational” planning, but that was exactly what they practiced. My generation enjoys the shade from a large oak tree today (Exxon’s dividends) because someone planted an acorn 100 years ago.

The families of my mother and father escaped Eastern Europe around 1900 as the idea of “central planning” was taking hold. They hailed from Poland, Lithuania, and the Austria-Hungry Empire (today’s Ukraine, Hungary, and Slovakia). Unfortunately for many of my relatives, they returned to the old country and got stuck there after WW1 and the Russian Revolution. As my grandfather used to say: “Johnny, I’d rather be lucky than good.” My family and I have benefited enormously from being lucky to be Americans.

Following WW2, many believed the central planning that won the war could also serve as a framework for economic prosperity. The United Kingdom tried it and nationalized coal, steel, and other industries. Japan focused on consumer products.

The UK strategy was a failure almost from the start. It took Margaret Thatcher’s courage and leadership in the 1980s to get the UK back on the free market path. Japan got lucky and their growth in the 80s caused many to think economic theory had been turned on its head. But when the music stopped, Japan’s luck was exposed. They couldn’t pivot.

Today, many think China’s approach has proven itself a path toward sustained growth, but I say they are missing the message of history. Free markets always win. Always…. always…always.

A few comments on today’s headlines:

A cottage industry has sprung up in the past decade with the sole focus of discrediting any good news on the economy. When President Obama was in office, the attacks mostly came from the Right. With the current occupant of the White House, the attacks mostly come from the Left. Since March 2009, regardless of who was in office, I have argued the economy will recover and will continue for longer than any of the pundits predicted.

The latest debate is over real (aka. inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP), which grew at a better-than-expected 2.1 percent annual rate in Q2. Some say it showed soft spots from the trade war and weak business investment. There is a lot of statistical noise in the exports/imports numbers, and the corrections down the road always change the numbers.

In my opinion, almost all the Q2 decline was due to a drop in “brick and mortar” investment (what economists call “structures”). In the age of the internet, software and computers are replacing brick and mortar. We buy airline tickets online, not in an office. Blockbuster was replaced by Netflix. You don’t need to leave the comfort of your own home, the stores come to you. As a result, investment in structures has slowed in recent years while investments in technology and equipment have continued to rise.

More importantly, business investment – when you remove structures – has picked up considerably under the current administration when compared to President Obama’s second term. Can you hear that sound in the distance? It’s the sound of my Fox News clients getting giddy while my CNN clients challenge me with the question, “why only use the final four years of the Obama presidency?” …

Here’s why. The first four years of Obama’s presidency were driven by a V-shaped recovery from the Panic of 2008. His second term illustrates the impact of tax hikes and more business regulation.

Real business investment – excluding structures – grew at a 3.8 percent annualized rate between Q4 2012 and Q4 2016, but accelerated to a 5.9 percent annualized rate since our current president took office. Real investment in software and R&D grew at a 5.5 percent annualized rate in the final four years of the Obama administration versus 7.5 percent since the start of 2017. Tax cuts and deregulation have boosted “animal spirits.”

GDP is growing, corporate profits are widely beating expectations. The economy is much stronger than conventional wisdom would have you believe, and it has been since 2009. Which brings me to the first two rounds of the Democratic debates.

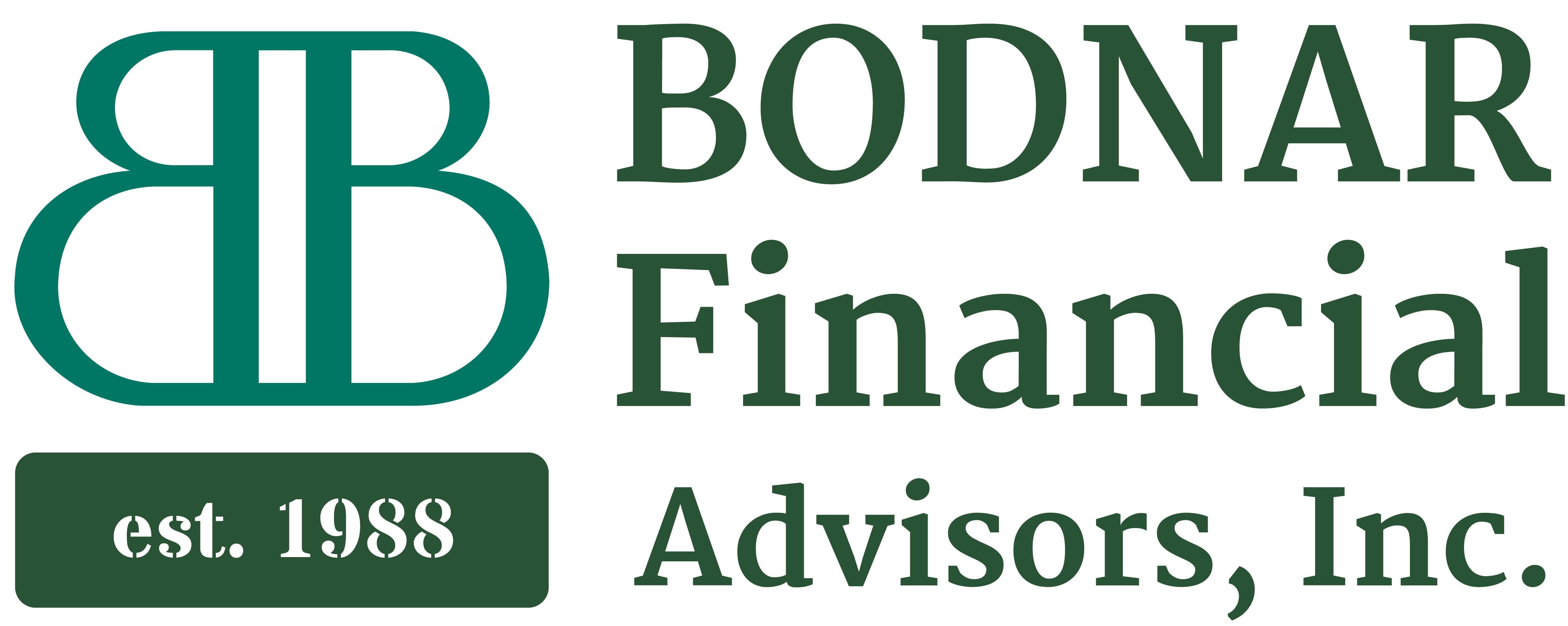

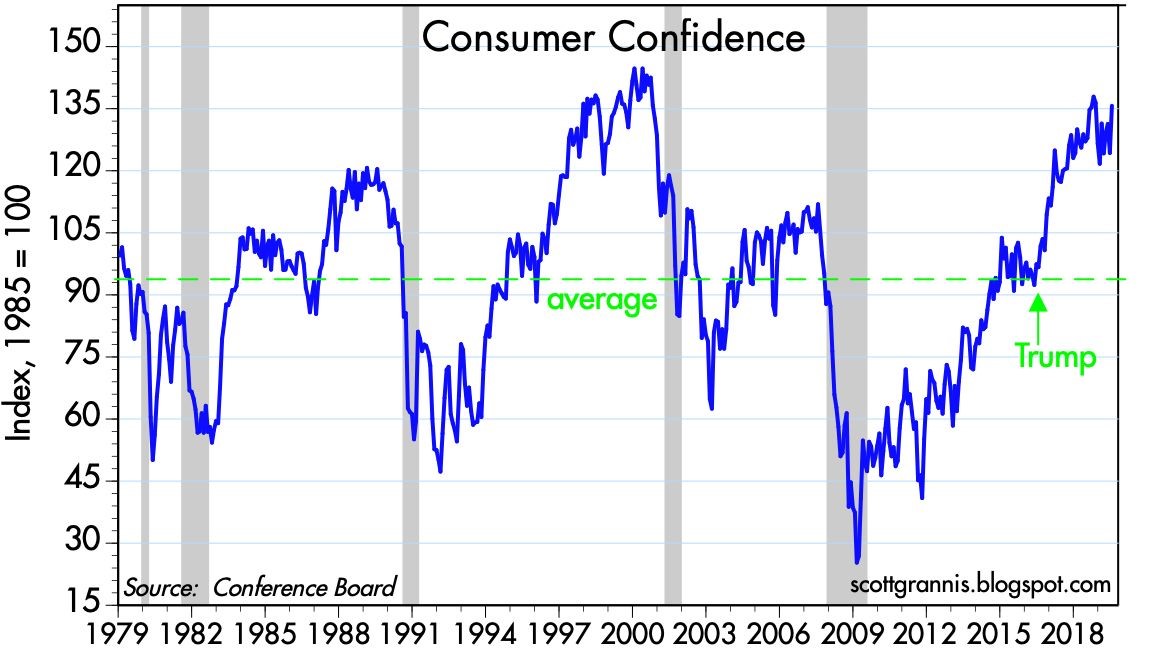

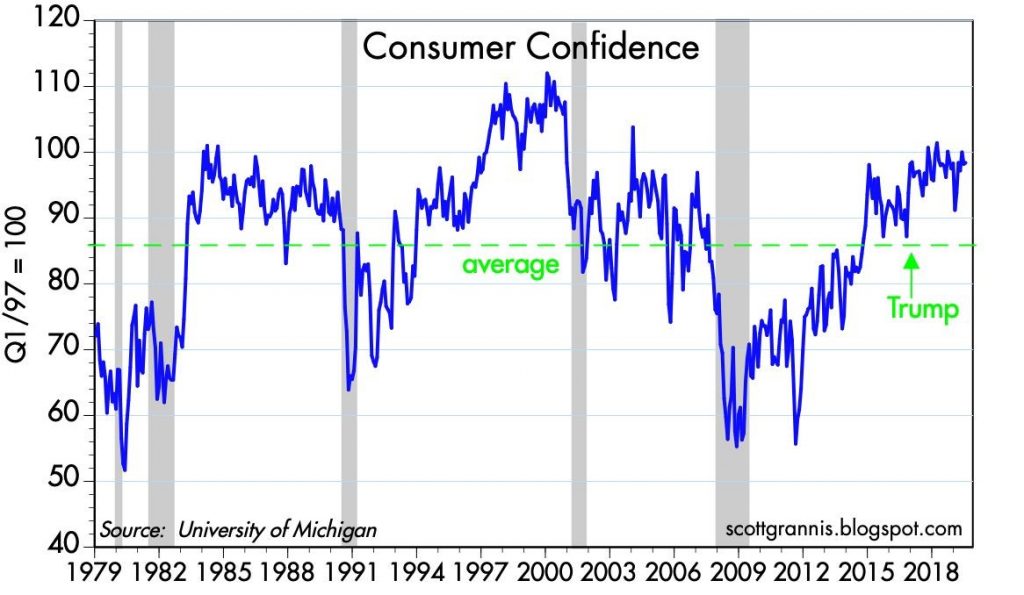

Consumer confidence these days is approaching record-high levels, and the impetus to the current surge in confidence can be traced to Trump’s election in late 2016. Democratic challengers are going to have tough times ahead convincing voters that a fundamental restructuring of the American economy is needed.

These charts show the three most widely followed indices tracking consumer confidence. All dates are as of July 2019:

While I would like to keep the persona – and even the name – of the incumbent U.S. president out of the discussion to the greatest extent possible, it is impossible to ignore the data. Unemployment stands at record lows, GDP is growing, and household net worth are at all-time highs. The greatest phenomenon of all (and largely ignored by the media) is that household debt service payments as a percentage of disposable income are at historically low levels.

I keep hearing James Carville’s dictum “The economy, stupid.” These economic realities will make it a very tough campaign for any of the challengers. Regardless of the outcome of the 2020 presidential election, we should embrace the fierce optimism of my late father and continue letting capital markets do some heavy lifting.

There is no single human being on this earth who can halt innovation and progress. Not even the president of the United States. Government can impede the flow of capital, but it can’t dam capital up altogether. As Nick Murray put it best: “Presidents are transient, the national political temper is cyclical, but capital is forever rational in the long run.”

Vičnaja pamjat,

John Bodnar, CFP®, CIMA®